Not Dead, Just Recalibrating My Eyes

In the last few months I’ve had a number of exchanges with people who, it becomes evident, have gotten the idea that I’ve packed in this whole writing thing. It came up again last month, when I was on the Lovecraft eZine Podcast. That people bring this up with regret is a relief. Lots better than if it were freighted with joy: “Oh thank god! We thought this day would never come.”

This has all occurred in the wake of the recent-ish release of Black Hole Sundown, or maybe since it went up for pre-order. The publisher and I have both referred to it as likely my final collection, so I can see how someone might extrapolate that it’s a 600-page tombstone for everything that came before.

But, as Black Hole Sundown’s endnotes go on to elaborate, it’s likely to be the last work of its kind — that’s all. It’s about feeling that I’ve come to the end of a particular road. The map, the terrain, however … these are more expansive than any one road. I don’t regard this as anything other than making some considered changes in direction and focus.

Bullet points, then:

My interests have changed and evolved.

No, I’m not quitting writing.

Although, for a while, it did quit me.

The most important factor in all of this remains the same, and no doubt always will.

Yeah Yeah, I’m Repeating Myself

If you’ve made it to Black Hole Sundown’s endnotes, I get into this there. But maybe you haven’t yet. Maybe you never will. In which case:

I began thinking of these sorts of internal shifts as the Great Rewiring. The phrase evolved out of a succinct way of letting various colleagues know why I was declining to participate in a project they might reasonably have expected me to be interested in:

When you go through some sort of long ordeal, especially where mortality is involved, you can come out of it with some substantial rewirings.

A few years back I lost both parents, twenty-three days apart. Both deaths were sudden and unanticipated. Still, the three weeks before my dad’s death was its own kind of ordeal. The following three weeks, a deepening of that ordeal. Then it was my mom’s turn, and oh fucking hell, who ordered more ordeal?

A cycle was quickly established: Drop everything, travel 1000 miles to go deal with something bad, return home depleted, try to regain a bit of equilibrium … and then something worse would happen.

Two-plus months of that. The next twelve were almost entirely consumed by the seemingly endless demands of my role as Estate Executor, which in total took nearly three years before everything was wrapped up, the estate could finally be closed, and I was relieved of the title by the same court that had appointed me.

Somewhere early in that span, all sense of myself as a writer — this thing that had been a core identifier almost my entire life — slipped away. The tag didn’t feel as though it fit anymore. It felt as if it belonged, to use the title of a long-ago story, to some other me. I didn’t miss it, much less mourn it, because with it went the capacity to miss it.

This Wasn’t Supposed to Happen

This outcome was nothing I would ever have believed could transpire, because the drive to write, the love of having written, had been with me since second grade. It had always occupied the big swivel seat at the center of the command deck, so fundamental that I’d never doubted it would always be there. And now the seat was looking … unoccupied.

Hmm. Interesting. What am I now, without this foundational core?

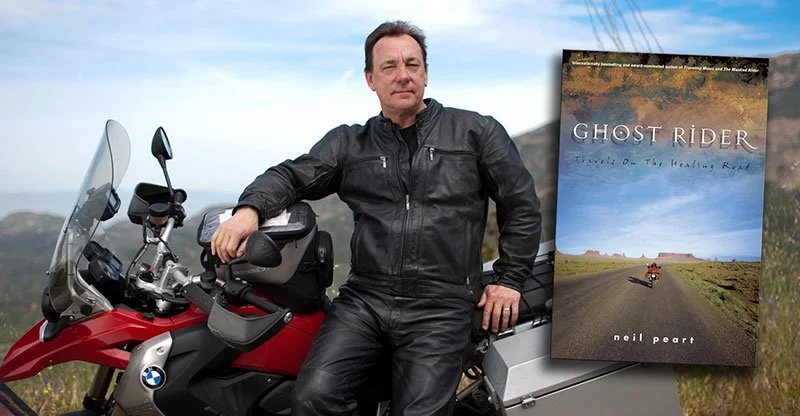

The first validation that, ahh, maybe this is normal, came while reading Ghost Rider, a memoir by Rush drummer/lyricist Neil Peart. It chronicles the years after he lost his family: first his daughter, to a car wreck; nine months later his wife, to cancer. I’d known, at the time, that the band was on extended hiatus, and why. But I’d not known the full extent of it: that Peart considered himself retired from drumming altogether.

Sometimes words leap off the page and grab us by the throat. In this instance it was Peart’s observation that those fundamental things he had always felt closest to — drumming and writing — were now the things that felt the farthest away.

Hmm. Interesting. I’m currently familiar with this inversion of reality.

At the time I contracted late-onset orphan syndrome, I was about 40% into writing a crowdfunded novel, A Song of Eagles. It remained at 40% for a long time. Every so often I would contemplate the responsibility I had to work on it, but found nothing inside to draw from, like trying to winch up water from a dry well. At various times I’ve thought of myself as a cottage industry; now the factory apparatus was dark, dismantled, disconnected from a power source.

It took awhile, but Neil Peart eventually made his way back to the drum throne. What I found equally intriguing — and relatable — was that he didn’t want to continue doing it the same way he’d been doing it before. He broke down his technique, rebuilt it from new fundamentals, and reinvented his approach to playing and performing.

Books — impacting lives a few vital words at a time.

For myself, after roughly the same timeframe — two years and some — it was as if all the lights came back on again. Over just a matter of days, unplanned and unexpected, the cottage lights came on again and the factory began cranking back to life.

Looks Exactly the Same, Only Totally Different

But now the place was changed. I’d lost interest in continuing to write the same sort of novels and stories I’d been best known for.

Moreover, I’d mostly lost interest in continuing with short-form works at all, in favor of focusing more or less exclusively on novels for the foreseeable future.

As those realizations sank in, there was a concurrent rise in fascination with something else: fantasy. To crib a couple lines from my on-site bio: The seeds were already there, in a handful of varied, atypical works I’d done in recent years. While I was busy elsewhere, the seeds sprouted and took over the garden.

Happily, A Song of Eagles was the perfect project to have waiting to be picked up again. I dove back into it and wrote the last 60% in two-and-a-half months. And absolutely loved it, even if the book has, sadly, turned into yet another lost work. The novel, its characters … they treated me better than the publisher ended up treating them. I’ll always have a soft spot for it, for how it confirmed for me that I could once more head in a different direction, and the process and engagement would continue to feel every bit as natural and alive.

Then again…

It’s not as clean a break as all that. There’s already been a relapse. This past March I finished a screenplay — all-out cosmic horror — that, months early, I’d been hired to write for a South American filmmaker, and loved the experience.

At the same time, I’ve been devoting more time than ever to working on music. Because it’s in there, and I love that process, too.

In this, one thing — what I consider the most important thing — remains the same as it ever was: I strive to devote as much time as is feasible to working on the projects that feel most compelling to work on. What lights up the synapses and keeps the passion on a rolling boil.

That, to me, is playing the long game: Maximum sources of contentment, minimal chances of burnout.

Somewhere early in that span, all sense of myself as a writer — this thing that had been a core identifier almost my entire life — slipped away.